04/09/2015

Andrew Huggins, The Table Spread

Written by Pendle Marshall-Hallmark

Even on a brisk Saturday afternoon in March, you can find Andrew Huggins at work on his tenacious garden at the corner of Westminster and 47th Streets in West Philly. All around the edges of what was once a dreary old basketball court, he’s managed to plant row upon row of tomatoes, watermelons, collard greens, squash, basil, pumpkins, and red cabbage. On the court itself, he’s got pots full of herbs, still hibernating under the recent snowfall. Soon, he says, he’s hoping to tear up the concrete altogether and replace it with even more food. In a far corner of the lot, just beyond the composting heap, he’s got an old banner that announces his venture to the neighbors passing by. It reads: “The Table Spread”.

An old childhood friend of Andrew’s is the Imam at the Philadelphia Masjid Mosque and school that borders the basketball court. When Andrew noticed the 3/4 acre piece of land just sitting there, he asked if he could use it to do some gardening. Since starting this venture back in 2010, around 17 people have joined him, working on their own plots within the space, and sometimes helping with communal crops. Whatever is produced goes to the neighbors, and anyone else the group can find to feed.

Andrew is a friendly giant of a man, and happy to share his extensive knowledge of horticulture with anyone who will listen. “For the longest time,” he explains, “I’ve liked playin’ in the dirt.” As a little boy, he would help his mother on her plot at the Mill Creek Garden Center at 46th and Brown, a less than 5 minute walk from where The Table Spread is now. But it wasn’t until a number of years ago that Andrew truly dove back into his love of gardening, and not for the reasons you might expect. He is blind, due to a degenerative eye condition called retinitis pigmentosa. Remarkably, it was this loss of the sense of sight that deepened his other senses, and, along with other reasons, drew him closer to gardening.

“You can hear the plants talkin’ to you, if you listen hard enough. They speak to the mind of the human being. You just have to listen in the right way.” Andrew’s keen senses of smell and touch are a huge aid to him in the garden—he explains that they can tell him when a plant is too dry or too wet, under or overripe, and everything in between. Becoming a successful gardener has been a step along the road to what he calls “self-identity”—it has given him a deeper sense of independence and strength.

For Andrew, gardening is about more than sunlight, rain, and vegetables. It’s about power, race, history, science and civilization. Humanity echoes the patterns found in nature; just look at the organizational structure of a beehive, he notes, or the rates of soil regeneration as compared with the skin of the human body (both take a total of 7 years to be completed). The history of slavery is tied up in horticulture, too—to illustrate this, Andrew tells the story of how slave traders bound for Charleston, South Carolina would use African watermelons to sustain the captives aboard their ships to the New World. Today, there is a variety of the plant that still carries the name “Charleston Gray”. A watermelon, of all things, is a reminder that for hundreds of years, slaves were made to work land that they did not own, and could not reap the benefits of.

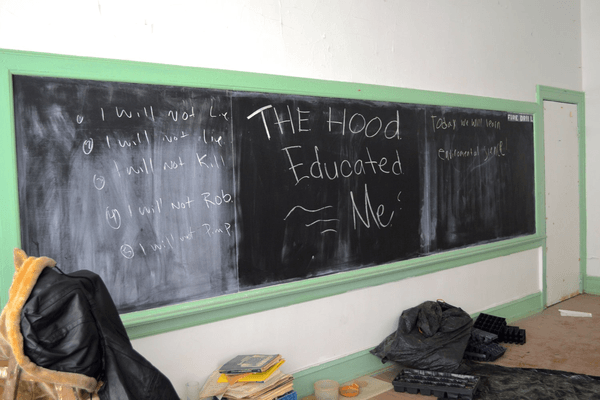

Andrew observes that there is still a deep stigma in the black community associated with farming and agricultural work. Because of its connection to slavery, “many people see it as a sort of weakness”, he explains, “Something they’re above doing.” He worries that many poor people of color are not aware of the danger in consuming foods that contain GMO’s and other processed elements. Andrew believes, and preaches fervently, that there is power in deciding to grow your own food, and that the process of gardening is therapeutic. He wishes that more people in his community associated gardening with self-sufficiency and strength, rather than subjugation and vulnerability.

A former Black Panther and member of the Worker’s Rights Law Project, Andrew is quickly able to articulate how this continued lack of access to healthy food is only a reflection of a larger problem. He notes that the black community in America has experienced a kind of economic, educational, political, and spiritual slavery, for which it has yet to be repaid. “We would like reparations for these types of slavery that we’ve been put through,” he explains, “and we would like control of our communities.” Andrew sees urban gardening as just one way to gain this kind of independence. He argues that there should be more support specifically for black farmers in Philadelphia, because “when you help the part of the whole that is struggling the most, you help to create a greater whole overall.” People knowing where their food comes from, and having power over what goes into their bodies, Andrew explains, is the first step towards building a stronger, healthier, more just, and more cohesive planet.